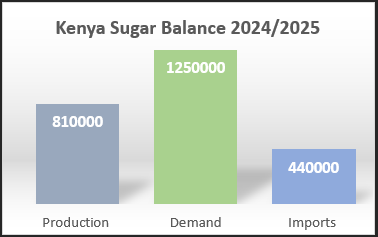

Kenya’s sugar sector is often framed in terms of scarcity, heavy imports, and mills that struggle to meet the demand. Yet this narrow view overlooks the immense potential of one of the country’s most versatile crops. In counties such as Kakamega, Bungoma, and Busia, sugarcane is more than just a sweetener; it is a strategic resource with the power to drive Kenya’s transition to a circular, green economy. In the 2024/25 season, Kenya harvested about 9.7 million tonnes of cane, yielding roughly 810,000 tonnes of sugar. National demand, however, exceeded 1.25 million tonnes, forcing the country to rely on imports. Forecasts for 2025/26 point to further contraction in sugar output, to around 650,000 tonnes, due to reduced cane area and lower extraction rates. These trends highlight a critical truth: the future of the sugar sector does not depend solely on producing more sugar, but on extracting greater value from every stalk of cane.

The by-products of sugarcane hold untapped promise. Bagasse, the fibrous residue left after crushing, can be used for power generation. Molasses can be converted into ethanol for blending with petrol, reducing fuel imports and emissions. Furthermore, filter cake, a nutrient-rich residue, can be recycled as organic fertiliser to restore soil fertility. Globally, Brazil provides a compelling model. In 2024, it generated over 21,000 GWh of bioelectricity, nearly three-quarters of it from sugarcane residues. Companies such as Raízen are pioneering advanced “second-generation” ethanol production from bagasse and straw, opening new frontiers in efficiency and carbon reduction. Kenya, too, has made progress. The draft National Energy Policy (2025–2034) estimates a cogeneration potential of 300 MW from bagasse. This energy can supplement the national grid, providing cleaner power and diversifying revenue streams. Examples in Kenya:

- Kwale International Sugar Company (KISCOL) – 18 MW cogeneration, drip irrigation yields up to 100 t/ha (double national average).

- Kibos Sugar – 3 MW onsite, expanding to 18 MW; diversifies into ethanol and paper production.

- Mumias Sugar – once ran 38 MW power and produced 20–22M litres of ethanol annually; its collapse shows the risks of poor governance.

The 2024 Sugar Act reestablished the Kenya Sugar Board and created a dedicated research institute, signalling renewed political will to stabilise and modernise the industry. Kenya currently has 17 operational mills and nearly 320,000 smallholder farmers, who cultivate 93% of the nation’s cane, typically on plots smaller than a hectare. This decentralised structure provides a strong foundation for a just transition if diversification into energy, fertiliser, and feed translates into better incomes and timely payments for farmers. As Jude Chesire, CEO of the Kenya Sugar Board, has noted, ensuring that lease and concession fees flow back to growers will be critical as mills expand into energy and ethanol ventures. In January 2025, the government prioritised domestic use of molasses for ethanol production. A national blending mandate, like Brazil’s adoption of E30 fuel (30% ethanol), could make ethanol a mainstream energy source in Kenya. Such a policy would cut fuel import bills, enhance energy security, and create thousands of green jobs.

Kenya vs Brazil-Cane Utilisation (2024)

| By-Product Use | Kenya | Brazil |

| Bagasse Power | 193 MW (mostly captive) | 21,218 GWh |

| Ethanol Blending | Minimal | 30% (E30 mandate) |

| Farmer Base | 320,000 smallholders | Large estates + Cooperatives |

The vision is clear: modern integrated sugarcane hubs in regions like Trans Nzoia and Narok, where mills not only produce sugar but also:

- Supply renewable electricity to rural communities.

- Manufacture ethanol for transport and industrial use.

- Produce organic fertiliser and livestock feed from filter cake and spent wash.

This model would create multiple revenue streams, shield farmers and mills from volatile sugar prices, and embed resilience in the wider economy. The benefits of such diversification extend beyond the sector. For farmers, it means better seed, irrigation investment, and reliable payments. For the nation, it means a cleaner power grid, reduced petroleum imports, and the emergence of a new class of rural green jobs. Kenya does not need to produce more sugar to make its cane sector viable. It needs to produce more value. By turning bagasse into electricity, molasses into ethanol, and filter cake into fertiliser and by tailoring lessons from Brazil to its own context, Kenya can transform its cane belt into a powerhouse of sustainable growth.